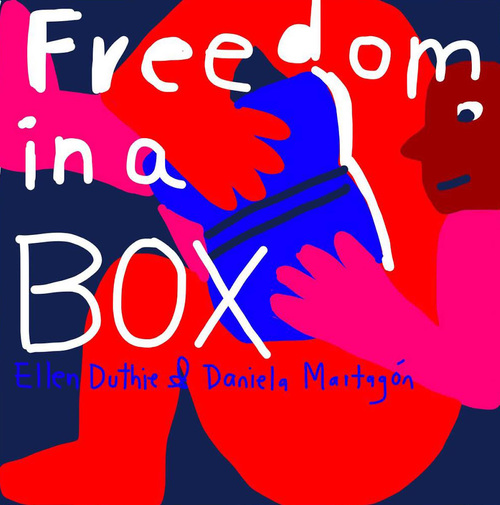

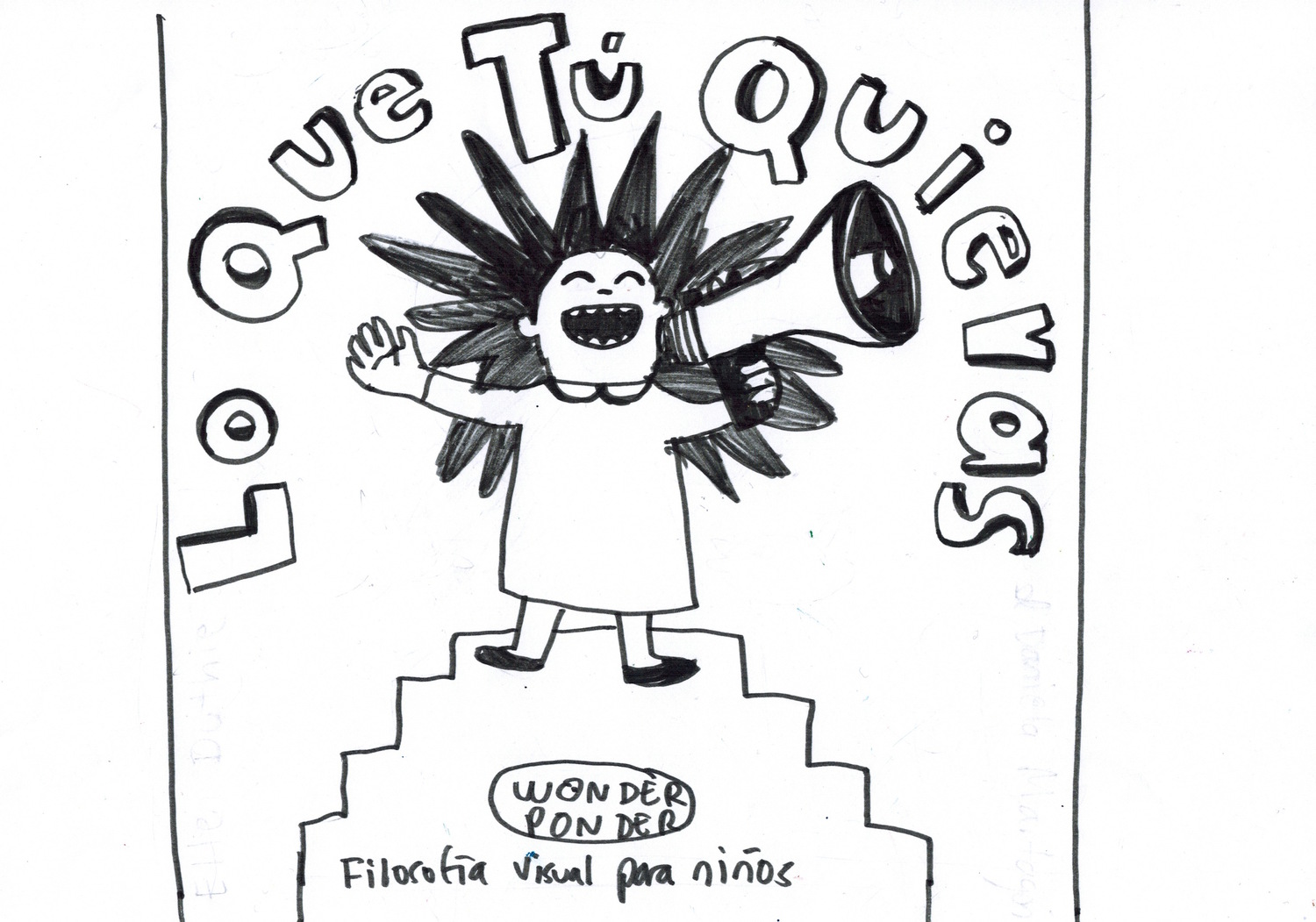

Competition! Win a copy of our Visual Philosophy for Children title on freedom, 'Whatever You Want'

Ellen Duthie

What?

A competition!

What's the prize?

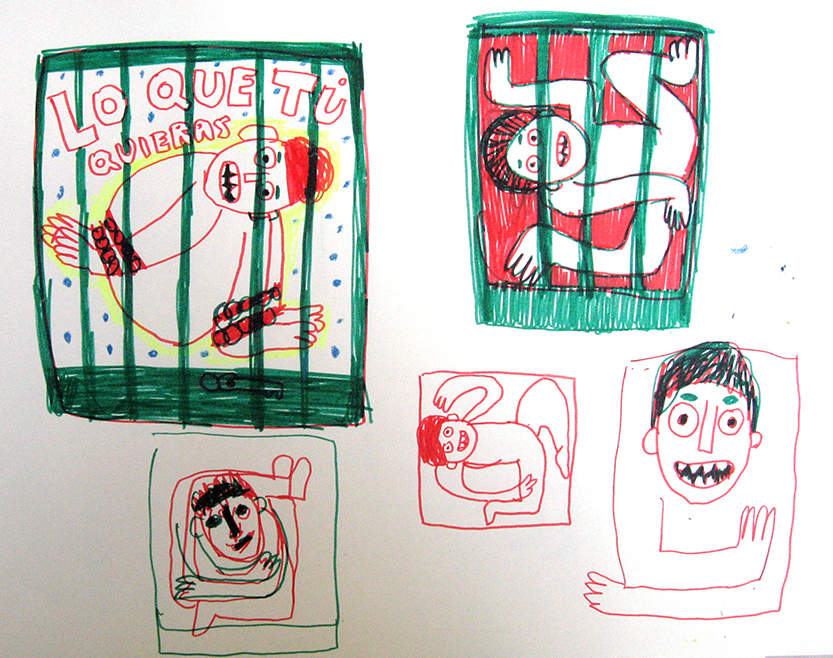

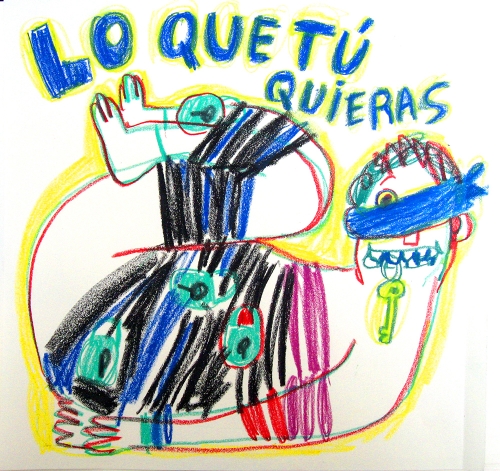

A copy of Whatever You Want, of our Visual Philosophy for Children book-in-a-box, specially signed and dedicated by the authors, with a drawing by the illustrator, Daniela Martagón? We'll send it wherever you tell us to!

Whatever You Want is an invitation to wonder and ponder about freedom for small, medium and large people. Half-way between a book and a game, it comes in a box and invites readers to think about freedom in a way that is both serious and seriously fun. Through the questions prompted by the scenes in the box, the reader-player can go building their own definition of freedom. Part of our critically acclaimed Wonder Ponder, Visual Philosophy for Children series, Whatever You Want is designed for children to look at, read and think playfully about by themselves, accompanied by an adult or in a group, in educational, play or family contexts.

What do I have to do?

It's easy! Look carefully at all the inhabitants of the Free House (the poster from Whatever You Want) and find at least 10 references to characters from children's literature (you'll see it's chock-a-block!).

When you've spotted ten characters, go to our Facebook page and leave a comment on this post, indicating your 10 characters, with the titles of the books they appear, the authors of the books and the room in the Free House where you found them (at the bottom of the poster you'll see a numbered list of all the rooms and spaces inside the house).

Remember! Your answer should be the list of the 10 characters you've found, with corresponding titles, authors and location within the house, and you should send us your answer as a comment on our Facebook page.

The draw from among all correct answers will take place on Friday 28th of October 2016. Good luck!

Need some tips? The poster features characters from Jumanji, by Chris Van Allsburg, from The Tiger Who Came to Tea by Judith Kerr, In the Night Kitchen by Maurice Sendak, I Want My Hat Back, by Jon Klassen, from Conrad, the Factory-made Boy, by Christine Nostlinger, from Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak... and from many, many, many more books. Enjoy!

What was the prize again?

A copy of Whatever You Want, of our Visual Philosophy for Children book-in-a-box, specially signed and dedicated by the authors, with a drawing by the illustrator, Daniela Martagón? We'll send it wherever you tell us to!